‘We have reached a stage in society where showing emotion is often hidden, discreet, or even seen as shameful.’

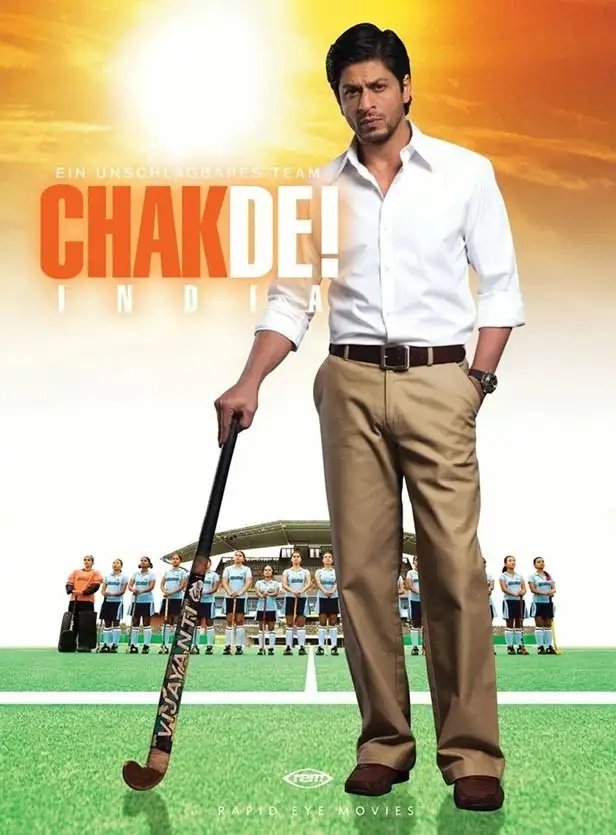

IMAGE: Jacob Elordi in Frankenstein.

Renowned Mexican filmmaker Guillermo Del Toro has been fascinated by monsters and their narratives since childhood.

Del Toro, who has directed 13 films primarily centered around monsters, has won three Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director for The Shape of Water (2017).

His previous works, such as Hellboy (2004), Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), and Crimson Peak (2015), served as preparation for a film he has wanted to create since age 11: Frankenstein, inspired by Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.

The film debuted at the Venice Film Festival and is currently available on Netflix.

Frankenstein has garnered numerous awards this season and is nominated for five Golden Globes, including Best Director for Del Toro.

Recently, Del Toro was honored at the Marrakech International Film Festival for his impact on global cinema.

During an interview with Aseem Chhabra, Del Toro discussed his passion project, highlighting how Frankenstein reflects both his vision and a tribute to Shelley’s book.

The interview took place at Marrakech’s historic La Mamounia Hotel, where Alfred Hitchcock filmed scenes for The Man Who Knew Too Much in 1956.

Guillermo, you mentioned wanting to make Frankenstein since you were 11. Were you not frightened by Shelley’s book as a child? Your monsters, like the Creature in Frankenstein, are not terrifying but rather endearing and emotional.

I was born in 1964. At that time, in Japanese Kaiju films, the giant monsters were charming.

Godzilla started as a symbol of nature’s power or the atomic bomb.

However, by the ’60s, Godzilla had become a hero.

When I read Frankenstein in the ’70s, it was a different culture.

Universal Monsters, distributed by Universal Pictures, were seen as heroes by new generations. By my time, monsters were appealing and beautiful.

In Shelley’s book, the monster is demonic in one instance when he strangles young William and says, ‘I loved it.’

This represents an outsider’s rage, but it’s rare in the book.

Mostly, the book resembles Caliban’s monologue in The Tempest where he questions why he was made this way.

The monster pleads with God, asking why he was created without understanding the world, which moved me deeply.

Raised Catholic, though now lapsed, I found the cosmology intriguing.

Mary Shelley uses ‘Paradise Lost’ as a philosophical anchor for her novel.

IMAGE: Oscar Isaac in Frankenstein.

Could you elaborate on your passion for this project? You created the Creature with a father, not a mother. How did it begin, and how does it feel to complete it?

At seven, I first saw James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931).

After church on Sundays, we watched movies at home.

Seeing Boris Karloff as the Monster was a religious experience for me.

I identified with the Creature, feeling I didn’t belong in the world, just like him.

At 11, I found a paperback of Shelley’s book and read it in one sitting, feeling I had discovered the best book ever.

I was already making Super Eight movies by eight, so I felt destined to make this film.

It took me 50 years to finally tell the Creature’s story, exploring its religious and philosophical themes.

For decades, I researched the Shelleys and Godwins, identifying with Mary Shelley and her background.

My own experiences with absent maternal figures resonated with the novel’s themes.

I grew up with stories lacking mothers, like Disney tales, where family dynamics were always fractured.

This influenced my interpretation of Frankenstein, fusing my biography with Shelley’s narrative.

Over time, I gathered ideas and collaborators for this film, culminating in a satisfying achievement.

IMAGE: Oscar Isaac in Frankenstein.

The influence of Lord Byron, a friend of Percy Bysshe Shelley, is evident in the film. You end with a Byron quote: ‘Thus the heart will break, yet brokenly live on.’

Byron is a powerful influence.

I modeled Oscar Isaac’s character after Byron and John Keats, a doctor-turned-poet.

The Creature’s journey mirrors Byron’s ‘Pathless Woods’ from Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

I sought to evoke the emotions I felt reading Shelley’s book at 11, rather than a mere homage.

How did you know Jacob Elordi would be perfect for the Creature?

His eyes and his understanding of the role convinced me.

Jacob expressed a deep connection with the Creature, feeling judged by his appearance, reflecting the loneliness of the character.

You’ve mentioned Kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery, as an inspiration for the Creature. How did this influence your design?

I explored Wabi-sabi, the beauty of imperfection, while working on Pan’s Labyrinth and Pacific Rim.

Storytelling is like Kintsugi, where we mend our broken selves with stories.

The Creature’s design reflects this philosophy.

IMAGE: Oscar Isaac in Frankenstein.

What about your relationship with fellow Mexican filmmakers Alfonso Cuaron, Alejandro Iñárritu, and Michel Franco?

I frequently communicate with Alfonso and Alejandro, more than with my own family.

We’re from the same generation, bonded by our rebellious spirit as young filmmakers.

We pushed for technical excellence and supported each other through challenges.

Michel Franco, a later addition, is also part of this supportive network.

We collaborate closely, sharing insights and feedback.

Despite perceived success, we’ve faced gaps and challenges, supporting each other throughout our careers.

IMAGE: Guillermo Del Toro. Photograph: Aseem Chhabra

What are your thoughts on AI in filmmaking?

AI should not replace human creativity and emotion.

It’s crucial to maintain the human spirit in art, resisting reliance on algorithms that lack genuine intelligence.

Victor Frankenstein’s arrogance mirrors the unchecked ambitions of AI developers.

The Romantic movement’s resistance to industrialization remains relevant today, underscoring the need for human connection.

Do you watch films in other genres?

My film collection is mostly comedies and dramas.

Emotion is important to me, and I believe it’s often undervalued in modern culture.

I wanted Frankenstein to feel emotionally resonant, like an opera.

Photographs curated by Satish Bodas/Rediff